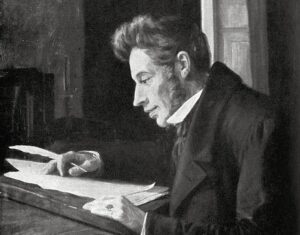

Parlare di Berserk – e soprattutto parlarne filosoficamente, è un po’ come camminare su di un campo pieno zeppo di mine che esplodono al suono dei passi: non potrai mai uscirne illeso senza che qualcuno abbia, contestualmente, da ridire. Mi ripeterò successivamente: Berserk è una delle opere provenienti dall’oriente più complesse, intricate, difficili, crude e violente che siano mai state prodotte; pertanto, ognuno recepisce il proprio contenuto in modo assai differente. Inoltre, il fatto che – purtroppo e con grande angoscia, il manga (perché effettivamente la versione animata è indietro ed anche non gli rende minimamente onore) non sia ancora concluso (ed il primo numero risale al 1989[1]), certamente non chiarisce punti – soprattutto filosofico-narrativi, che altrimenti, lapalissianamente, sarebbero più chiari. Personalmente, credo, in modo quasi certo, che questo sia il lavoro più difficile che mai abbia presentato ed al quale mai abbia lavorato: le motivazioni non sono tanto derivanti dalla difficoltà insé dell’argomentazione in questione, quanto dal fatto che vi sia un’affezione fortissima nei confronti di quest’opera la quale, forse più di qualsiasi altra, è riuscita a portarmi ad una maturazione effettiva. Pertanto, sicuramente sarà un lavoro sentito e pregno di emozione, ma cionondimeno oggettivo e rigoroso, come sempre lo sono stati gli altri da me presentativi. “[…] e vergogna io non ho di dire il vero,/di confessare quanto tedio io senta/per questo viver mio pien di tormento” – Tibullo, Elegie (dal Corpus Tibullianum), Libro III, II[2] Ritengo davvero che questa terzina (nella sua trasposizione italiana) delinei perfettamente il contesto che stiamo accingendoci a trattare: Tibullo – o chi per lui, qui esprime, con impudicizia, sincerità e schiettezza, con grande senso del vero, quanto il vivere sia pieno di tormento, e quanto, di questo tormento, non si debba avere vergogna. Credo fortemente che, se vi fosse una parola la cui semantica allacci completamente, come un cappio, l’intero concetto dietro un’opera tanto complessa come quella di Berserk, sia proprio questa: tormento. L’intera narrativa berserkiana è sussumibile sotto la categoria del tormento e della disperazione: come canonico in senso kierkegaardiano, la disperazione porta con sé la necessita dell’io, porta con sé la necessità di essere-sé-stessi; i personaggi di Berserk , praticamente tutti, kierkegaardianamente disperano, e grazie a questa disperazione, a questo squassante struggimento interiore del proprio spirito, intuiscono la necessità del proprio io.

A differenza dello scorso pezzo che vi abbiamo proposto, il quale tendeva ad analizzare filosoficamente un’opera che è anche filosofica[3] – seppure fosse lo stesso autore che, in modo anche provocatorio, spesso e volentieri ne inseriva citazioni e rimandi – Berserk si configura in modo decisamente più manifesto ed evidente come opera di tipo filosofico.  L’interezza della narrazione si basa su motivazioni ponderate meticolosamente e su riflessioni talmente tanto introspettive da essere alle volte nebulose non solo per il lettore, ma anche per lo stesso personaggio che riflette il quale, pur comprendendo il proprio obiettivo, non ne focalizza a fondo le pulsioni che lo animano[4]. Introdurre Berserk credo sia ben più difficile di introdurre qualsiasi altra opera nipponica: la mole di contenuti è abissale, la narrativa è molto complessa e si confà di più saghe le quali hanno sempre al centro un tema eterogeneo rispetto a quello precedente ed a quello succedente, ed ogni momento diegetico è scandito da una grande spannung costante, da un senso asfissiante e permanente presente di fiato sul collo e di pericolo; Berserk si legge costantemente col fiato sospeso: tecnicamente, potremmo dire che l’opera non abbia un climax vero e proprio perché l’interezza della narrazione è costituita da avvenimenti focali e centrali. Berserk è un climax. Conscio di questo, e conscio del fatto che la stragrande maggioranza dei lettori del presente non avrà potuto – fatelo se ne avete l’opportunità, godere dell’opera, vedremo questa sotto gli occhi della filosofia kierkegaardiana ed heideggeriana: queste due, considerate nella loro valenza esistenzialista rispetto alla prima, progettualista rispetto alla seconda, riescono a rendere una lettura di superficie – ed al contempo perimetrica, soddisfacente nella misura in cui faccia presentire l’enormità mancante e faccia, spero, venire la curiosità di scoprirla. Nello specifico, prenderemo in considerazione i due protagonisti dell’opera, Gatsu e Grifis[5], i quali costituiscono, assieme agli altri personaggi, la ruota che muove il carro narrativo. L’opera è cronologicamente inserita all’interno di un medioevo fittizio – che non manca di citazioni storiche, dove la guerra, la miseria, e la sottomissione, sono la convenzione: in Berserk non c’è spazio per momenti felici, e quei pochi che ci sono rasentano l’onirico per quanto estremamente brevi e caduchi, effimeri, essendo repentinamente succeduti da avvenimenti struggenti. In questo medioevo abbiamo un mercenario fuoriclasse, Gatsu, il quale non conosce vita che non abbia il suo senso nella spada e nell’uccidere per sopravvivere, e Grifis, anch’egli mercenario, che, al contrario di Gatsu che vive per uccidere, uccide per vivere e per realizzare un sogno tanto grande quanto apparentemente irrealizzabile: da mercenario qual è, vorrebbe un suo regno, vorrebbe ascendere le classi sociali fino ad acquisire tanto potere quanto gli basta; per fare questo, è pronto a tutto. A seguito di un duello, Gatsu diventa proprietà di Grifis[6], ed è costretto a seguirlo nel suo sogno, divenendo parte dell’Armata dei Falchi, gruppo mercenario di cui Grifis è il capo. Da qui in poi si aprono vari spiragli narrativi – alcuni prolissi, altri decisamente brevi – i quali, oltre ovviamente a far proseguire la narrazione in sé e per sé, delineano in modo preciso e determinato il tema filosofico al centro dell’opera, o quantomeno della prima parte dell’opera[7]: capire il proprio posto nel mondo, non accontentarsi di essere heideggerianamente gettati al mondo e, dandosi un progetto, inseguirlo con ogni mezzo, perché quello è il senso della vita, della propria vita, della vita di ogni singolo individuo in quanto egli, nella sua irripetibile singolarità, è la verità di sé stesso, e del mondo, in quanto quel mondo è sé stesso nella misura in cui ci vive e, quando muore, sparisce.

L’interezza della narrazione si basa su motivazioni ponderate meticolosamente e su riflessioni talmente tanto introspettive da essere alle volte nebulose non solo per il lettore, ma anche per lo stesso personaggio che riflette il quale, pur comprendendo il proprio obiettivo, non ne focalizza a fondo le pulsioni che lo animano[4]. Introdurre Berserk credo sia ben più difficile di introdurre qualsiasi altra opera nipponica: la mole di contenuti è abissale, la narrativa è molto complessa e si confà di più saghe le quali hanno sempre al centro un tema eterogeneo rispetto a quello precedente ed a quello succedente, ed ogni momento diegetico è scandito da una grande spannung costante, da un senso asfissiante e permanente presente di fiato sul collo e di pericolo; Berserk si legge costantemente col fiato sospeso: tecnicamente, potremmo dire che l’opera non abbia un climax vero e proprio perché l’interezza della narrazione è costituita da avvenimenti focali e centrali. Berserk è un climax. Conscio di questo, e conscio del fatto che la stragrande maggioranza dei lettori del presente non avrà potuto – fatelo se ne avete l’opportunità, godere dell’opera, vedremo questa sotto gli occhi della filosofia kierkegaardiana ed heideggeriana: queste due, considerate nella loro valenza esistenzialista rispetto alla prima, progettualista rispetto alla seconda, riescono a rendere una lettura di superficie – ed al contempo perimetrica, soddisfacente nella misura in cui faccia presentire l’enormità mancante e faccia, spero, venire la curiosità di scoprirla. Nello specifico, prenderemo in considerazione i due protagonisti dell’opera, Gatsu e Grifis[5], i quali costituiscono, assieme agli altri personaggi, la ruota che muove il carro narrativo. L’opera è cronologicamente inserita all’interno di un medioevo fittizio – che non manca di citazioni storiche, dove la guerra, la miseria, e la sottomissione, sono la convenzione: in Berserk non c’è spazio per momenti felici, e quei pochi che ci sono rasentano l’onirico per quanto estremamente brevi e caduchi, effimeri, essendo repentinamente succeduti da avvenimenti struggenti. In questo medioevo abbiamo un mercenario fuoriclasse, Gatsu, il quale non conosce vita che non abbia il suo senso nella spada e nell’uccidere per sopravvivere, e Grifis, anch’egli mercenario, che, al contrario di Gatsu che vive per uccidere, uccide per vivere e per realizzare un sogno tanto grande quanto apparentemente irrealizzabile: da mercenario qual è, vorrebbe un suo regno, vorrebbe ascendere le classi sociali fino ad acquisire tanto potere quanto gli basta; per fare questo, è pronto a tutto. A seguito di un duello, Gatsu diventa proprietà di Grifis[6], ed è costretto a seguirlo nel suo sogno, divenendo parte dell’Armata dei Falchi, gruppo mercenario di cui Grifis è il capo. Da qui in poi si aprono vari spiragli narrativi – alcuni prolissi, altri decisamente brevi – i quali, oltre ovviamente a far proseguire la narrazione in sé e per sé, delineano in modo preciso e determinato il tema filosofico al centro dell’opera, o quantomeno della prima parte dell’opera[7]: capire il proprio posto nel mondo, non accontentarsi di essere heideggerianamente gettati al mondo e, dandosi un progetto, inseguirlo con ogni mezzo, perché quello è il senso della vita, della propria vita, della vita di ogni singolo individuo in quanto egli, nella sua irripetibile singolarità, è la verità di sé stesso, e del mondo, in quanto quel mondo è sé stesso nella misura in cui ci vive e, quando muore, sparisce.

Il tema dei primi 26 volumetti italiani di Berserk è quindi il sogno, o, in modo decisamente più contestualmente heideggeriano, il progetto: il senso autenticizzante l’esistenza è il rendersi conto del proprio essere-per-la-morte, e proprio in virtù di questa consapevolezza ottenuta, comprendere la necessità di una verità che venga da dentro e che dia forma alla propria esistenza altrimenti inautentica. Grifis incarna perfettamente questa consapevolezza: si rende conto dell’essere-per-lamorte dell’uomo, comprende quanto la morte stessa sia dell’uomo l’ineluttabile fine, e gli pare così evidente la necessità di vivere seguendo un senso che possa non certo garantirgli l’immortalità, quanto rendergli l’esistenza nella sua autenticità più pura; avendo compreso la morte, ora deve comprendere la vita, la quale non è solamente in funzione della morte, se autentica. Se heideggerianamente ogni uomo comprende l’essenza dell’essere nella sua autenticità in virtù della morte, del niente, rivelandone i tratti individuali nel progettualismo, la riflessione berserkiana fa un passo in avanti, gettando questa riflessione metafisico-esistenzialista all’interno di un contesto etico ed interpersonale: inseguire il proprio progetto, il proprio sogno, significa calpestare quello dell’altro, inevitabilmente.

Ogni sogno, ogni progetto, prevede la resistenza del progetto o del sogno altrui, perché ogni uomo, anche flebilmente ed in modo velleitario, ha un sogno il quale, tanto più grande è, tanto più porterà a calpestare quello degli altri che si parano contro il proprio; ed anche nella sua potenziale infinita piccolezza, il sogno, il progetto, è sempre tendente all’esterno – anche se in virtù dell’interno, ed in quanto tale è sempre tangente uno altrui:  dallo scontro, solamente un sogno, solamente un progetto, potrà vedere la luce[8], potrà continuare ad esistere. Parlando del sogno, infatti, Grifis sostiene che sia “qualcosa che non si fa per nessuno e che si realizza… si realizza solo per sé stessi. […] c’è chi sogna di dominare il mondo, chi dedica tutta la vita alla creazione di una spada, e se c’è un sogno a cui sacrificare tutto sé stessi… c’è anche un sogno che, simile ad una tempesta, spazza via migliaia di altri sogni. […] il sogno ci sostiene e ci fa soffrire, il sogno ci salva e ci uccide. E poi, dopo averci abbandonato, le sue ceneri rimangono sempre in fondo al cuore… fino alla morte… […] si nasce per caso, senza volerlo, e si trascorre una vita priva di significato… io non potrei mai sopportare un’esistenza simile.” (K. Miura, Berserk, n. 12, Marvel Manga, Modena, 1998). Introdotto in modo spero efficace, questo è il personaggio di Grifis: determinato e consapevole, insegue la vita dandole un senso avendo compreso il niente; viceversa, quello che poi sarebbe il reale protagonista dell’opera, Gatsu, non ha, come abbiamo visto, alcun progetto che non sia quello di uccidere per potersi guadagnare da vivere. Eppure, come facilmente intuibile, stare con Grifis, aprire il suo cuore all’Armata, lo muterà repentinamente: quella che era solo una sete di sangue si tramuterà in un desiderio di ricercare sé stesso che, poi, culminerà in una fase topica di cui – chiaramente, non vi parlerò per non rovinare la sorpresa. Se kierkegaardianamente Grifis potrebbe rappresentare l’eticità in quanto è colui il quale ha seriamente intrapreso una scelta che insegue e persegue nel tempo, Gatsu è ancora esteticamente intrappolato in una spirale di scelte non consapevolmente intraprese: insegue il piacere dell’uccisione, insegue il piacere del danaro – pur questo certamente servendogli per sostentarsi, e non ha altro scopo se non quello di vivere il momento, vivere nel momento, essendo il domani, poiché non progettato, indefinibile ed incerto. “[…] l’estetica nell’uomo è quello per cui egli spontaneamente è quello che è; l’etica è quello per cui diventa quello che diventa. […] Chi vive esteticamente non può dare della sua vita nessuna spiegazione soddisfacente, perché egli vive sempre solo nel momento, e ha una coscienza soltanto relativa e limitata di sé stesso” (S. Kierkegaard, Aut-Aut/Enten-Eller, Mondadori, Milano, 2016, pp. 27).

dallo scontro, solamente un sogno, solamente un progetto, potrà vedere la luce[8], potrà continuare ad esistere. Parlando del sogno, infatti, Grifis sostiene che sia “qualcosa che non si fa per nessuno e che si realizza… si realizza solo per sé stessi. […] c’è chi sogna di dominare il mondo, chi dedica tutta la vita alla creazione di una spada, e se c’è un sogno a cui sacrificare tutto sé stessi… c’è anche un sogno che, simile ad una tempesta, spazza via migliaia di altri sogni. […] il sogno ci sostiene e ci fa soffrire, il sogno ci salva e ci uccide. E poi, dopo averci abbandonato, le sue ceneri rimangono sempre in fondo al cuore… fino alla morte… […] si nasce per caso, senza volerlo, e si trascorre una vita priva di significato… io non potrei mai sopportare un’esistenza simile.” (K. Miura, Berserk, n. 12, Marvel Manga, Modena, 1998). Introdotto in modo spero efficace, questo è il personaggio di Grifis: determinato e consapevole, insegue la vita dandole un senso avendo compreso il niente; viceversa, quello che poi sarebbe il reale protagonista dell’opera, Gatsu, non ha, come abbiamo visto, alcun progetto che non sia quello di uccidere per potersi guadagnare da vivere. Eppure, come facilmente intuibile, stare con Grifis, aprire il suo cuore all’Armata, lo muterà repentinamente: quella che era solo una sete di sangue si tramuterà in un desiderio di ricercare sé stesso che, poi, culminerà in una fase topica di cui – chiaramente, non vi parlerò per non rovinare la sorpresa. Se kierkegaardianamente Grifis potrebbe rappresentare l’eticità in quanto è colui il quale ha seriamente intrapreso una scelta che insegue e persegue nel tempo, Gatsu è ancora esteticamente intrappolato in una spirale di scelte non consapevolmente intraprese: insegue il piacere dell’uccisione, insegue il piacere del danaro – pur questo certamente servendogli per sostentarsi, e non ha altro scopo se non quello di vivere il momento, vivere nel momento, essendo il domani, poiché non progettato, indefinibile ed incerto. “[…] l’estetica nell’uomo è quello per cui egli spontaneamente è quello che è; l’etica è quello per cui diventa quello che diventa. […] Chi vive esteticamente non può dare della sua vita nessuna spiegazione soddisfacente, perché egli vive sempre solo nel momento, e ha una coscienza soltanto relativa e limitata di sé stesso” (S. Kierkegaard, Aut-Aut/Enten-Eller, Mondadori, Milano, 2016, pp. 27).

Proprio questa “coscienza soltanto relativa e limitata di sé stesso”, una volta rivelatasi in tutta la sua devastante crudezza, porterà Gatsu ad intraprendere un cammino che lo condurrà a cercare sé stesso; gli renderà manifesta, proprio come lo era per Grifis, la necessità di dare un senso alla sua esistenza, senso che non fosse quello di appoggiare un progetto, un sogno, altrui.[9] La caratterizzazione apparentemente superficiale del carattere di Gatsu sarà mano a mano approfondita fino a rivelarsi quasi più complessa – complice la crudissima dietrologia della sua vita, di quella dell’amico[10] Grifis: non bisogna assolutamente pensare, in modo del tutto fuorviante, quindi, che la personalità di Gatsu si esaurisca entro la semplice categoria del carnefice poi rinsavito; il ritmo dell’approfondimento psicologico è forse lento e scandito da una pesantezza narrativa, eppure anche il personaggio di Gatsu diventa estremamente caratterizzato, soprattutto non più pensando alle prime fasi narrative, quanto alle successive. “Cosa diavolo sto facendo… in un posto così schifoso? Per chi rischio la mia vita?” (K. Miura, Berserk, n. 13, Marvel Manga, Modena, 1998)[11] La consapevolezza ottenuta porterà Gatsu verso degli eventi che rivoluzioneranno non solamente la sua esistenza, ma anche lo stesso mondo nel quale egli è gettato: il suo porsi seriamente – eticamente, nella scelta, troverà, come anticipato, la resistenza del sogno altrui, del sogno di Grifis, per la realizzazione del quale egli, Gatsu, è un necessario tassello; scontro dal quale, purtroppo ma necessariamente, non potrà che uscirne solamente uno in grado di proseguire nel proprio progetto. Speriamo che questa tanto prolissa quanto auspicabilmente interessante disquisizione vi faccia venir voglia di scoprire quale.

NOTE:

1: L’opera risulta essere tanto longeva – o prolissa, non tanto per il fatto che abbia molto da narrare o che abbia un universo espanso gigantesco (anche), quanto per i vari iati che l’autore, per una motivazione o per l’altra, decide di prendersi.

2: Quest’elegia viene attribuita a Ligdamo, pseudonimo sotto il quale gli studiosi ritengono vi sia lo stesso Tibullo, o addirittura un giovane Ovidio.

3: Parliamo de “La Filosofia in Neon Genesis Evangelion, per una metafisica dell’anime”.

4: Questo è del tutto berserkianamente canonico, essendo il suo universo pervaso da una forza arcana, il fato, che tanto restituisce quella sensazione di Τύχη classica spesso e volentieri presente nel mondo poetico-letterario greco.

5: Data l’estrema facilità dell’opera – ed è lapalissiano io stia scherzando, anche sui nomi, molto spesso, vi sono incongruenze, non tanto dettate dall’opera in-sé quanto da una traslitterazione dal Giapponese alle volte fedele ed alle volte meno nelle varie traduzioni: in inglese, ad esempio, Gatsu verrà reso Guts, Grifis verrà traslitterato come Griffith, ed il medesimo discorso è applicabile a praticamente tutti i personaggi dell’opera dando, purtroppo, alle volte, un effetto spiazzante. Noi stiamo utilizzando la traslitterazione dal giapponese più fedele, ossia quella rinvenibile nella prima edizione originale del manga italiano.

6: “D’ora in poi sei mio!” (K. Miura, Berserk, n. 8, Marvel Manga, Modena, 1997); questo è quanto Grifis dice a Gatsu dopo averlo letteralmente sottomesso: ad oggi, anche per successivi avvenimenti narrativi decisamente contorti e complessi, il rapporto Gatsu-Grifis è oggetto di – molto spesso accese, disquisizioni circa la natura del sentimento – specialmente quello di Grifis nei confronti di Gatsu – che li anima. Alcuni sostengono un platonismo di fondo sublimante la sfera fisica abbracciando una ideale; altri vedono nel loro rapporto un rimando al sentimento filiaco presente nei poemi epici – pensare ad Achille e Patroclo nell’Iliade – classici; ancora, altri ci vedono una vera e propria omosessualità; altri ancora vedono solamente un utilitarismo mirante a coinvolgere emotivamente Gatsu nella realizzazione di intenti personali. Come ora deducibile evidentemente, l’opera è decisamente complessa e piena di sfaccettature.

7: La parte che stiamo analizzando, infatti, costituirebbe, tassonomicamente parlando, quella che viene definita “Golden Age”: narrativamente, essa è un’enorme analessi che ha il compito di contestualizzare l’incipit in medias res dei primi numeri.

8: Purtroppo per questioni di spazio, e di altrimenti prolissità insostenibile – e già la presente mi rendo conto sia pesante, non si può approfondire ulteriormente la questione; eppure non vorrei certamente peccare di incompletezza, pertanto, voglio comunque rendere evidente come, la seguente riflessione basantesi sullo scontro violento di due sogni, di due progetti, sia decisamente affine alla logica tanto eraclitea quanto soprattutto hegeliana: postasi la cosa, alla stessa sarà contrapposto un negativo dal quale inevitabile scontro si avrà un superamento (hegelianamente aufhebung) che ingloba in-sé quello stesso negativo.

9: In Berserk è evidente anche la posizione sveviana dell’inetto, ossia di colui il quale non sa comportarsi dinnanzi alla vita, di colui che non sa vivere: berserkianamente, colui che non sa trovare un senso al proprio esistere, si appoggia al progetto altrui divenendo metaforicamente come un falò che tenta di alimentare una fiamma più grande e calda la quale, a sua volta, tiene in vita quella più fioca. (Cfr. n. 14, Marvel Manga edizioni)

10: Rendiamo in corsivo il termine “amico” poiché sarà soprattutto una riflessione sull’amicizia fatta da Grifis a far comprendere a Gatsu il valore del sogno, del progetto, e la necessità di dare un senso determinato alla propria esistenza (vedi n.12, Marvel Manga edizioni). Secondo altre interpretazioni, Gatsu, scegliendo di ricercare sé stesso, non vorrebbe fare altro che essere davvero amico di Grifis, essendo per quest’ultimo, amico, un suo pari; pari il quale non ha alcun tipo di timore o remore nel contrastare anche il sogno dell’amico (anzi, sarebbe proprio questo a fare l’amicizia), pur di vedere il proprio realizzato. Filosoficamente, vorrei evidenziare come una similissima riflessione sia scorgibile nella filosofia kierkegaardiana, dove l’amico è colui il quale condivide con un altro la medesima concezione di vita (cfr. S. Kierkegaard, Aut-Aut/Enten-Eller, Mondadori, Milano, 2016, pp. 187), e quindi, berserkianamente, qualcuno che reputiamo un nostro pari, poiché animato dalla nostra medesima intenzionalità.

11: Di questa citazione, tratta dal manga – di per sé rappresentante la massima canonicità, vorrei riportarne, poiché secondo me più determinatamente descrivente i pensieri di Gatsu nel momento, la controparte animata: “Che cosa ci faccio qui, conciato come un miserabile, a condurre una vita ignobile?” (Berserk, episodio 14, 1997).

Simone Santamato

—————————————————————————————————————————

KIERKEGAARDIAN EXISTENTIALISM AND HEIDEGGERIAN

PROJECTUALISM IN BERSERK

A necessary preamble:

The text that is just presented to you is a translation of a previously published work initially

available exclusively in Italian. In order to maintain and totally preserve the original text – even

though it is self-evident by adopting the appropriate adaptations, the piece will be a one-to-one

translation of the original work. In this sense, even the citations, which may differ from the original

English version, have been translated literally from the Italian version; therefore, in the case of

differences – as great as they are minimal, we now know the cause is considered and consciously

evaluated. Thanking you for your interest in the piece, so much so that we decided on a translation –

which we hope will be reliable and error-free (in case we apologize), we wish you a good reading.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Talking about Berserk – and especially talking about it philosophically, is a bit like walking on a

field full of mines that explode at the sound of your footsteps: you can never get out of it unharmed

without someone objecting at the same time. I will repeat myself later: Berserk is one of the most

complex, intricate, difficult, crude and violent works from the East that have ever been produced;

therefore, everyone perceives its content very differently. Moreover, the fact that – unfortunately

and with great anguish, the manga (because actually the animated version is behind and also does

not do it any honour) is not yet finished (and the first issue dates back to 1989[1]), certainly does

not clarify points – especially philosophical-narrative ones, which would be otherwise, of course, be

clearer.

Personally, i believe, almost certainly, that this is the most difficult work i have ever presented and

worked on. The reasons for this are not much due to the difficulty of the argument itself, but rather

to the fact that there is a very strong affection for this work which, perhaps more than any other, has

managed to bring me to a real maturity. Therefore, it will certainly be a heartfelt and emotional

work, but nonetheless objective and rigorous, as has always been the case with the others i have

presented.

“[…] and i am not ashamed to tell the truth,/to confess how much tedium i feel/for this life of mine

full of torment” – Tibullus, Elegies, (from the Corpus Tibullianum), Book III, II[2].

I truly believe that this triplet (in its Italian transposition) perfectly delineates the context we are

about to deal with: Tibullus – or whoever he is here, expresses, with impudence, sincerity and

frankness, with a great sense of the truth, how much life is full of torment, and how, of this torment,

one should not be ashamed. I strongly believe that if there were a word whose semantics would

completely tie, like a noose, the entire concept behind a work as complex as Berserk, it would be

this one: torment.

The whole of Berserk’s narrative can be subsumed under the category of torment and despair: as

canonical in the kierkegaardian sense, despair brings with it the necessity of the self, it brings with

it the necessity of being oneself; the characters of Berserk, practically all of them, despair in a

kierkegaardian way, and thanks to this despair, to this shattering inner torment of their own spirit,

they sense the necessity of their own self.

Unlike the last piece we proposed to you, which tended to philosophically analyse a work that is

also philosophical[3] – even if it was the same author who, in a provocative way, often inserted

quotations and references, Berserk is decidedly more manifest and evidently a philosophical work.

The entire narrative is based on meticulously pondered motivations and on such introspective

reflections as to be at times nebulous not only for the reader, but also for the reflecting character

himself who, although understanding his objective, does not fully focus on the drives that animate

him[4].

I think that introducing Berserk is much more difficult than introducing any other Japanese work:

the amount of content is enormous, the narrative is very complex and it is made up of several sagas

that always have at their centre a heterogeneous theme with respect to the previous one and the

following one, and every diegetic moment is marked by a great constant spannung, by a suffocating

and permanent sense of breath on one’s neck and of danger; Berserk can be read constantly with

bated breath : technically, we could say that the work has no real climax because the entirety of the

narrative consists of focal and central events. Berserk is a climax.

Conscious of this, and conscious of the fact that the vast majority of the readers of the present work

will not have been able – do it if you have the opportunity, to enjoy the work, we will look at it

through the eyes of kierkegaardian and heideggerian philosophy: these two, considered in their

existentialist value with respect to the first, and projectualist with respect to the second, succeed in

making a surface reading – and at the same time a perimetric one, satisfactory to the extent that

hints at the missing enormity and, i hope, arouses the curiosity to discover it. Specifically, we will

consider the two protagonists of the work, Guts and Griffith[5], who constitute, together with the

other characters, the wheel that moves the narrative wagon.

The work is chronologically inserted inside a fictitious Middle Ages – which is not lacking in

historical quotations, where war, misery, and submission are the convention: in Berserk there is no

room for happy moments, and those few that are there border on the oneiric because they are

extremely brief and fleeting, ephemeral, being suddenly succeeded by poignant events. In this

Middle Ages we have an outstanding mercenary, Guts, who knows no life that does not have its

meaning in the sword and in killing to survive, and Griffith, also a mercenary, who, unlike Guts

who lives to kill, kills to live and to realize a dream as great as apparently unattainable: as the

mercenary he is, he would like to possess his own kingdom, he would like to ascend the social

classes up to acquire as much power as he needs; to do this, he is ready to do anything.

Following a duel, Guts becomes the property of Griffith[6], and is forced to follow him in his

dream, becoming part of the Band of the Hawk, a mercenary group of which Griffith is the leader.

From here onwards, various narrative vistas open up – some of them long, others decidedly short –

which, apart from obviously continuing the narrative in and of itself, outline in a precise and

determined manner the philosophical theme at the centre of the work, or at least of the first part of

the work[7]: to understand one’s place in the world, not to be content with being heideggerianally

thrown into the world and, giving oneself a project, to pursue it by all means, because that is the

meaning of life, of one’s own life, of the life of each individual insofar as he, in his unrepeatable

singularity, is the truth of himself, and of the world, insofar as that world is itself to the extent that

he lives in it and, when he dies, disappears.

The theme of the first 26 italian volumes of Berserk is therefore the dream, or, in a decidedly more

contextually heideggerian way, the project: the authenticating meaning of existence is to become

aware of one’s own being-for-death, and precisely by virtue of this awareness obtained, to

understand the need for a truth that comes from within and gives form to one’s otherwise

inauthentic existence. Griffith embodies this awareness perfectly: he realizes man’s being-for-death,

he understands how death itself is man’s inescapable end, and so it becomes clear to him the need to

live according to a meaning that may not guarantee him immortality, but rather render his existence

in its purest authenticity; having understood death, he must now understand life, which is not only a

function of death, if it is authentic.

If heideggarianally every man understands the essence of being in its authenticity in virtue of death,

of nothingness, revealing its individual traits in projectualism, Berserk’s reflection takes a step

forward, throwing this metaphysical-existentialist reflection within an ethical and interpersonal

context: pursuing one’s own project, one’s own dream, means trampling on that of the other,

inevitably. Every dream, every project, foresees the resistance of the project or the dream of others,

because every man, even feebly and unrealistically, has a dream which, the greater it is, the more it

will lead to trampling on that of other who parade themselves against their own; and even in its

potential infinite smallness, the dream, the project, is always tending towards the outside – even if

by virtue of the inside, and as such is always tangential to that of others: from the clash, only a

dream, only a project, can see the light[8], can continue to exist.

Speaking of the dream, in fact, Griffith maintains that is “something that you do for no one and that

you realize… your realize only for yourself. […] there are those who dream of dominating the

world, those who dedicate their whole lives to the creation of a sword, and if there is a dream to

which they sacrifice their whole selves… there is also a dream which, like a storm, sweeps away

thousands of other dreams. […] the dream sustains us and makes us suffer, the dream saves us and

kills us. And then, after abandoning us, its ashes always remain at the bottom of our hearts… until

we die… […] one is born by chance, without wanting it, and spends a life without meaning… i

could never bear such an existence.” (K. Miura, Berserk, no. 12, Marvel Manga editions, Modena,

1998)

Introduced in a hopefully effective way, this is the character of Griffith: determined and aware,

pursues life by giving it meaning having understood nothing; vice versa, the one who is actually the

real protagonist of the work, Guts, has, as we have seen, no plan other than to kill in order to make a

living.

And yet, as can be easily guessed, being with Griffith, opening his heart to the Hawks, will change

him abruptly: what was only a thirst for blood will turn into a desire to search for himself,

culminating in a topical phase of which – clearly, i won’t mention it so as not to spoil the surprise.

If, in a kierkgaardian way, Griffith could represent ethically in that he is the one who has seriously

undertaken a choice that he pursues and pursues in time, Guts is still aesthetically trapped in a spiral

of choices not consciously undertaken: he pursues the pleasure of killing, he pursues the pleasure of

money – although this certainly serves him to sustain himself, and he has no other aim than to live

in the moment, because tomorrow is, since it is not planned, indefinable and uncertain.

“Aesthetics in man is that by which he spontaneously is what he is; ethics is that by which he

becomes what he becomes. […] He who lives aesthetically can give no satisfactory explanation of

his life, because he always lives only in the moment, and has only a relative and limited

consciousness of himself” (S. Kierkegaard, Aut-Aut/Enten-Eller, Mondadori, Milan, 2016, pp. 27).

It is precisely this “only relative and limited awareness of himself”, once revealed in all its

devastating harshness, that will lead Guts to embark on a path that will lead him to search for

himself; it will make manifest to him, just as it was for Griffith, the need to give a meaning to his

existence, a meaning that is not that of a supporting a project, a dream, of others.

The apparently superficial characterization of Guts’ character will gradually deepen until it reveals

itself to be almost more complex – thanks to the cruel dietrology of his life, that that of his

friend[10] Griffith: therefore, it is not at all misleading to think that Guts’ personality is exhausted

within the simple category of the executioner who then comes to his senses; the rhythm of the

psychological deepening is perhaps slow and marked by a narrative heaviness, yet Guts’ character

also becomes extremely characterized, especially not thinking of the first narrative phases, but of

the following ones.

“What the hell am i doing… in such a lousy place? Who am i risking my life for?” (K. Miura,

Berserk, no. 13, Marvel Manga editions, Modena, 1998) [11]

The awareness obtained will bring Guts towards events that will revolutionize not only his

existence, but also the very world in which he is thrown: his serious – ethical, choice will find, as

anticipated, the resistance of the dream of others, of the dream, in this case, of Griffith, for the

realization of which he, Guts, is a necessary element; a clash from which, unfortunately but

necessarily, only one is able to continue his own project can come out. We hope that this longwinded

but hopefully interesting disquisition will make you want to find out which one.

NOTES

1: The work turns out to be so long – or long-wided, not so much because it has a lot to tell or has a

gigantic expanded universe (even), but because of the various hiatuses that the author, for one

reason or another, decides to take.

2: This elegy is attributed to Ligdamus, a pseudonym under which scholars believe Tibullus

himself, or even a young Ovid.

3: We are referring to “La Filosofia in Neon Genesis Evangelion, per una metafisica dell’anime”.

4: This is completely canonical in berserkian terms, because his universe being pervaded by an

arcane force, fate, which so much restores that feeling of classical Τύχη often and willingly present

in greek poetic-literary world.

5: Given the extreme easiness of the work – and it’s obvious that i’m joking, also on the names,

very often, there are inconsistencies, not so much dictated by the work itself as by a transliteration

from Japanese, sometimes faithful and sometimes less in the various translations; in Italian, for

example, Guts will be rendered Gatsu, Griffith will be transliterated as Grifis, and the same thing is

applicable to almost all the character of the work giving, unfortunately, sometimes, a disorientating

effect.

6: “From now you are mine” (K. Miura, Berserk, no. 8, Marvel Manga, Modena, 1997); this is what

Griffith says to Guts after he has literally subdued him. To this day, also because of subsequent

narrative events that are decidedly convoluted and complex, the Guts-Griffith relationship is the

subject of – very often heated, disquisitions about the nature of the feelings – especially Griffith’s

ones toward Guts – that animate them. Some argue for an underlying Platonism sublimating the

physical sphere by embracing an ideal one; others see in their relationships a reference to the

philiacal feeling present in the classical epics – think of Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad; still,

others see a real homosexuality in it. Still others see only an utilitarianism aimed at involving Guts

emotionally in the realization of personal goals. As can now evidently be deduced, the work is

decidedly complex and multifaceted.

7: The part we are analyzing, in fact, would constitute, taxonomically speaking, what is called the

“Golden Age”: narratively, it is an enormous flashback whose task is to contextualize the incipit in

medias res of the first issues.

8: Unfortunately, for reasons of space, and of otherwise unbearable prolixity – and i already realize

that this one is heavy, we cannot go into the matter any further; yet, i certainly would not like to sin

of incompleteness, therefore, i would still like to make it clear how, the following reflection based

on the violent clash of two dreams, of two projects, is decidedly akin to both heraclitean and

especially hegelian logic: once the thing has been posed, it will be countered by a negative from

which the inevitable clash will lead to a surpassing (in hegelian terms, aufhebung) that incorporates

that same negative in itself.

9: In Berserk, the svevian position of the inept is also evident, that is to say of he who does not

know how to behave in front of life, of he who does not know how to live: in berserk’s terms, he

who does not know how to find a meaning to his own existence, relies on the project of others,

becoming metaphorically like a bonfire that tries to feed a larger and hotter flame which, in turn,

keeps the dimmer one alive. (Cf. no. 14, Marvel Manga editions).

10: We make the term “friend” italicized because it will be above all a reflection on friendship

made by Griffith that will make Guts understand the value of the dream, of the project, and the need

to give a determined meaning to his own existence (see no. 12, Marvel Manga editions). According

to other interpretations, Guts, choosing to search for himself, would like nothing more than to be a

true friend of Griffith, being for the latter, a friend, an equal; an equal who has no fear or qualms

whatsoever in opposing even his friend’s dream (indeed, it is precisely this that would make for

friendship), in order to see his own dream realized. From a philosophical point of view, i would like

to point out that a very similar reflection can be seen in Kierkegaard’s philosophy, where the friend

is someone who shares the same conception of life with another (cf. S. Kierkegaard, Aut-Aut/EntenEller,

Mondadori, Milan, 2016, pp.187), and therefore, in the manner of Berserk, someone whom

we consider our equal, since he is animated by our same intensions.

11: Of this quote, taken from the manga – itself representing the highest canonicity, i would like to

quote its animated counterpart, since in my opinion it more clearly describes Guts’ thoughts in the

moment: “What am i doing here, looking like a wretch, leading an ignoble life?” (Berserk, episode

14, 1997).